Historical Perspective

Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four | Part Five | Part Six | References

|

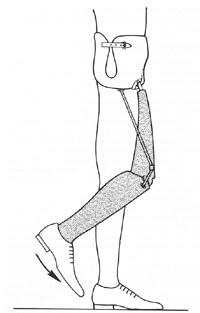

FIG21B-3 Canadian prosthesis in the early swing phase. The hip joint remains neutral as the shank swings forward. (From Michael J: Clin Prosthet Orthot 1988; 12:99108. Used by permission.) |

|

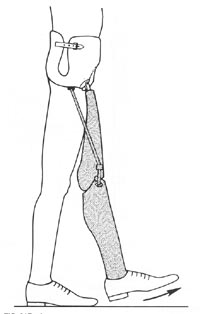

FIG21B-4 Canadian prosthesis just after midswing. The hip joint does not flex until shank motion is arrested by the terminal extension stop. As a result, the prosthesis is fully extended at the instant of midswing, which makes toe clearance difficult. (From Michael J: Clin Prosthet Orthot 1988, 12:99-108.Used by permission.) |

|

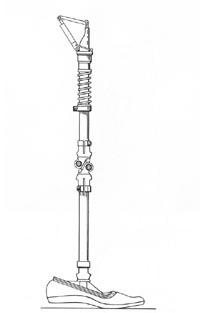

FIG21B-5 Hip flexion bias system developed by Haslam et al of Houston. Note the compression spring encircling the thigh tube, which propels the limb forward during the swing phase. (From Michael J: Clin Prosthet Orthot 1988; 12:99-108.Used by permission.) |

|

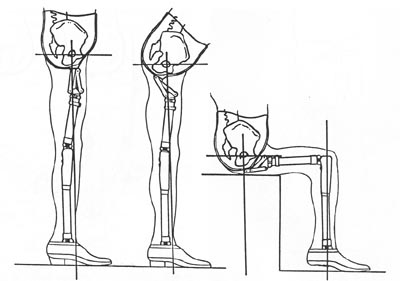

FIG21B-6 Schematic motion permitted by using an inverted polycentric knee joint as a hip mechanism, first advocated by Tuil of the Netherlands. |

Knee Joint Mechanisms

Other than the exception discussed above, knee mechanisms are selected by the same criteria as for transfemoral (above-knee) amputees. The singleaxis (constant-friction) knee remains the most widely utilized due to its light weight, low cost, and excellent durability. Friction resistance is often eliminated to ensure that the knee reaches full extension as quickly as possible. A strong knee extension bias enhances this goal and offers the patient the most stable biomechanics possible with this mechanism.

Although the singleaxis type was proposed as the knee of choice for the Canadian hip disarticulation design, more sophisticated mechanisms have proved their value and are gradually becoming more common. The friction-brake stance control (safety) knee is probably the second most frequently utilized component. Because there is very little increase in cost or weight and reliability has been good, many clinicians feel that the enhanced knee stability justifies this approach, particularly for the novice amputee. Missteps causing up to 15 degrees of knee flexion will not result in knee buckle, which makes gait training less difficult for the patient and therapist.

The major drawback to this knee is that the limb must be nonweight bearing for knee flexion to occur. Although this generally presents no problem during swing phase, some patients have difficulty in mastering the weight shift necessary for sitting. It should be noted that use of such knee mechanisms bilaterally must be avoided. Since it is impossible for the amputee to simultaneously unload both artificial limbs, sitting with two stance control knees becomes nearly impossible. A third type that has proved advantageous for this level of amputation is the polycentric (four-bar) knee. Although slightly heavier than the previous two types, this component offers maximum stance-phase stability. Because the stability is inherent in the multilinkage design, it does not erode as the knee mechanism wears during use.

In addition, all polycentric mechanisms tend to "shorten" during swing phase, thus adding slightly to the toe clearance at that time. Many of the endoskeletal designs feature a readily adjustable knee extension stop. This permits significant changes to the biomechanical stability of the prosthesis, even in the definitive limb. Because of the powerful stability, good durability, and realignment capabilities of the endoskeletal polycentric mechanisms, they are particularly well suited for the bilateral amputee. Patients with all levels of amputation, up to and including translumbar (hemicorporectomy), have successfully mambulated with these components.

At first glance, a manual locking knee seems a logical choice. However, experience has shown that this is rarely required and should be reserved as a prescription of last resort. Only additional medical disabilities such as blindness will require this mechanism. Unlocking the knee joint in order to sit requires the use of one hand in the unilateral case; expecting a hilateral amputee to cope with dual locking knees and dual locking hips is unrealistic. Furthermore, in the event of a fall backwards, fully locked joints may prevent the amputee from bending his trunk to protect his head from impact.

For many years, the use of fluidcontrolled knee mechanisms for highlevel amputees was considered unwarranted since these individuals obviously walked at only one (slow) cadence. The development of hip flexion bias mechanisms and more propulsive foot designs have challenged this assumption. Furthermore, a more sophisticated understanding of the details of prosthetic locomotion has revealed an additional advantage of fluid control for the hiplevel amputee. It is well accepted that any fluid control mechanism (hydraulic or pneumatic) results in a smoother gait. Motion studies conducted at Northwestern University have confirmed that a more normal gait for the hip disarticulation/transpelvic amputee is also produced. Gait analysis has demonstrated that utilization of a hydraulic knee in a hip disarticulation prosthesis results in a significantly more normal range of motion at the hip joint during the walking cycle than is possible with conventional knees.

In addition, a more rapid cadence was also possible. The preferred mechanism has separate knee flexion and extension resistance adjustments. A relatively powerful flexion resistance limits heel rise and initiates forward motion of the shank more quickly. In essence, the limb steps forward more rapidly. As the shank moves into extension, the fluid resistance at the knee transmits the momentum up to the thigh segment and pushes the hip joint forward into flexion. In effect, the fluid controlled knee results in a hip flexion bias.

(Fig21B-7) Richard Lehneis et al. have reported on a coordinated hipknee hydraulic linkage using a modified Hydrapneumatic unit. This adaptation provides a hip extension bias and has resulted in a smoother gait(Fig21B-8) Finally, a number of new components have been developed recently that combine the characteristics of some of the above classes of knee mechanisms. For example, Teh Lin manufactures a "Graphlite" knee consisting of a polycentric unit with pneumatic swing phase control in a carbon fiber receptacle. Such "hybrid" designs are expected to increase over the next few years.

We have divided this article up into sections for faster load times as follows:

Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four | Part Five | Part Six | References